The Innocence Project

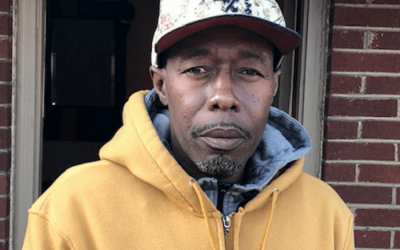

Chris Bennett is one of the many prisoners that the Innocence Project has proven innocent through the discovery of new evidence such as DNA. The Innocence Project has proven the innocence of 202 prisoners who have collectively spent nearly 2,500 years in prison for crimes they did not commit.

The Innocence Project was established in 1992 and has grown to more than 35 groups today, connected by the struggle to free wrongly convicted people. Using DNA testing technology and the help of law students, the Innocence Project reviews past criminal trials to determine if accused individuals were convicted under false pretenses.

The driving force of the program is the knowledge that there are numerous innocent prisoners sitting in jail with untold stories. Many of these stories are discounted because of bad eyewitness testimony and racism. According to the Innocence Project, of the wrongfully imprisoned people freed by the organization:

• 62% were African American.

• 48% of those misidentified were cross-racial, meaning a Caucasian victim would incorrectly identify an African American person.

• 14 of the misidentified men, who were later exonerated, were serving time on death row.

Aside from the hurdles of misidentification and race, the group still has to fight the prosecutors just to get to the evidence that may set innocent people free. The group spends most of its resources on litigation just to get the rights to test the evidence again, according to Mark Godsey, the Innocence Project’s faculty advisor at the University of Cincinnati’s College of Law.

“Most prosecutors don’t do additional DNA testing because of the cost,” said Godsey. “They make up their mind and become convinced right away of who’s guilty.”

Barry C. Sheck and Peter J. Neufeld founded the Innocence Project in 1992 at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University. The program has full-time attorneys with students to provide assistance to solve the cases. The organization is totally nonprofit and believes their mission is to reform the legal system that has imprisoned so many innocent people.

Even before the Innocence Project was created, a Columbia Law School study revealed that as many as 100,000 prisoners had been wrongly convicted because of the estimated 5% failure rate of the U.S. justice system.

DNA Testing

Chris Bennett is one of the many who had ample evidence to set themselves free but little means to defend themselves. Bennett lost his memory in a 2001 one-car accident that killed another man and pleaded guilty to aggravated vehicular homicide for a nine-year jail sentence. Bennett began to regain his memory in jail and wrote to the Innocence Project for help. The group reviewed the case and realized not only was there witness testimony, but also hair and blood to prove he wasn’t driving the car.

Bennett was exonerated in 2006.

“Our students got trained in collecting the samples, and we videotaped taking the sample,” Godsey said. “We did Y-STR DNA testing on the blood on the windshield and mitochondria DNA testing on the hair we found.”

Y-STR DNA testing is the most common type of testing done by the Innocence Project, and consists of determining whether two or more males are related through their paternal line. The mitochondrial DNA test is used to determine whether two or more individuals are related through their maternal line. University of Cincinnati’s College of Law’s Innocence Project sends their DNA samples to DNA Diagnostics Center’s laboratory in Fairfield, Ohio, to be tested.

With 65% of exonerated people sent to prison based on “fraudulent, unreliable or limited forensic science,” more DNA testing is necessary to cancel out bad witness.

Prisoner’s Defense

35 states have their own procedural rules for prisoners who would like to access DNA evidence from their case after being convicted. However, many states require new evidence to be brought to court within six months of conviction. This makes it nearly impossible for prisoners convicted before DNA testing was available to bring their suit to court.

In Bennett’s case, students tracked down the van involved in his accident at a junkyard, took the samples, and submitted them to a DNA testing lab for analysis. The DNA test placed Bennett in the passenger’s seat, not the driver’s seat.

Stark County Prosecutor John Ferrero listened to this new evidence, but in many instances, it is difficult to get prosecutors to listen to the Innocence Project’s new evidence. “Prosecutors generally oppose us helping, and I don’t know why,” Godsey said. “The evidence will point one way or the other.”

The team found both new eyewitness testimony and an accident-reconstruction expert who disputed the original verdict. Bennett was finally released in 2006, 4 years after he went to jail for a wrongful conviction.

Thankfully, Bennett’s case occurred after the 1980s when DNA evidence techniques weren’t nearly as strong as they are today. During the 1980s, police put a fluid on the DNA that they thought preserved the DNA, only to find out later that it actually aided in the deterioration of the sample, according to Godsey.

0 Comments